A 64-year-old woman with coarctation of aorta, earlier diagnosed as mild. Her medical history includes a history of secondary hypertension related to adrenal hyperplasia, hirsutism, polycystic ovaries, struma nodosa, diabetes mellitus. Patient reports no cardiac difficulties/symptoms.

Medical therapy for hypertension is sufficient.

Due to absence of clinical symptoms, well corrected hypertension and normal ejection fraction of non-hypertrophied left ventricle, patient is being monitored in an out-patient clinic without indication for invasive procedure.

Figure 1 ECG with sinus rhythm, incomplete RBBB, no signs of LVH

Video 1 TTE showing bicuspid aortic valve stenosis with significant calcification, coarctation of aorta with mild progression of gradients.

Figure 2 Peak systolic gradient of 70 mmHg

Clinical significance

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a discrete narrowing of the aorta near the site where the ductus arteriosus inserts. CoA is a relatively common defect that accounts for 5-8% of all congenital heart defects. Coarctation of the aorta may occur as an isolated defect or in association with various other lesions, most commonly bicuspid aortic valve and ventricular septal defect (VSD). This defect usually results in left ventricular pressure overload. It occurs more commonly in males than in females. The vast majority of cases are congenital.

Figure 3 A. Ductal B. Preductal (infantile type) C. Postductal (adult type)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7284000/

1. Clinical manifestation

- CoA does not cause a hemodynamic problem in utero as two-thirds of the combined cardiac output flows through the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) into the descending thoracic aorta, bypassing the site of constriction at the isthmus.

- Neonates may be asymptomatic if there is a persistent PDA or if CoA is not severe. When PDA closes, patients with severe defects may present with HF and/or shock.

- Older infants and children are often asymptomatic or present with hypertension, murmurs, or symptoms of chest pain or claudication.

- In previously undiagnosed adults hypertension is a very highlighted clinical sign. Most patients are asymptomatic unless severe hypertension is present, which may lead to headache, epistaxis, heart failure, or aortic dissection. Claudication of the lower extremities can occur due to reduced flow.

- The relative frequency of associated cardiac lesions differs somewhat based upon the age of the population studied. In general, less than one-quarter of patients with CoA have isolated CoA without associated cardiovascular abnormalities. In infants and children, a considerable proportion of patients have associated complex congenital heart disease. In adults, a bicuspid aortic valve is the most common associated defect.

- The classic findings of CoA are systolic hypertension in the upper extremities, diminished or delayed femoral pulses (brachial-femoral delay), and low or unobtainable arterial blood pressure in the low extremities.

- in most cases, the origin of the left subclavian artery is proximal to the coarctation, resulting in hypertension in both arms

- a blood pressure gradient between the upper and lower extremities >20 mm Hg indicates significant coarctation of the aorta

- A systolic murmur can extend beyond the second heart sound, at the left paravertebral interscapular area, due to flow across the narrow coarctation area. Continuous murmurs may be caused by flow through large collateral vessels.

Figure 4

- Patients with CoA who reach adolescence demonstrate very good long-term survival up to age 60 years. Long-term morbidity is common, however, largely related to aortic complications and long standing hypertension.

- Natural course complications are:

- left sided heart failure

- left ventricular hypertrophy

- intracranial aneurysms (the magnitude of risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage from rupture of intracranial aneurysms in patients with CoA is uncertain)

- intracranial hemorrhage

- Infective endocarditis

- aortic rupture/dissection

- premature coronary and cerebral artery disease

- associated heart defects

- Genetic tests for Turner syndrome should be performed in all girls diagnosed with CoA (approximately 5 to 15 percent of girls with CoA have Turner syndrome).

- The diagnosis of CoA

- initial workup includes blood pressure measurements in all four extremities

- generally confirmed by TTE (most often used in the assessment of cardiac disease but has limitations in evaluating extra cardiac structures and collateral circulation)

- MRI or CT are used as complementary diagnostic tool.They both depict the site, extent, and degree of the aortic narrowing, the aortic arch, the pre- and post-stenotic aorta, and collaterals. Both methods detect complications such as aneurysms, restenosis, or residual stenosis

- cardiac catheterization and angiography (CA) is the gold standard in assessing the pressure gradients across the CoA and provides high-resolution images of the aorta

- chest X-ray findings may be characterized by rib notching of the third and fourth (to the eighth) ribs due to the collaterals - collateral blood flow may involve the intercostal, internal mammary, and scapular vessels, which circumvents the stenotic lesion

Figure 5 Rib notching on X-ray

- The care of a patient with CoA depends upon the severity of the CoA, patient age, and clinical presentation.

- surgical resection is the treatment of choice in neonates, infants and young children

- in older children (> 25 kg) and adults, transcatheter treatment is the treatment of choice

Indications for intervention (surgical or transcatheter) are:

- peak to peak coarctation gradient ≥ 20 mmHg

- radiographic evidence of significant collateral flow

- coarctation-attributed systemic hypertension

- coarctation-attributed heart failure

- exercise limitations from limited lower extremity blood flow (i.e., claudication)

References

- Law MA, Tivakaran VS. Coarctation of the Aorta. [Updated 2020 Nov 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430913/

- Agasthi P, Pujari SH, Tseng A, et al. Management of adults with coarctation of aorta. World J Cardiol. 2020;12(5):167-191. doi:10.4330/wjc.v12.i5.167

- 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease (previously Grown-Up Congenital Heart Disease. European Heart Journal (2021), doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554 https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Grown-Up-Congenital-Heart-Disease-Management-of

- Ziyad M Hijazi. Clinical Manifestations and diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta. UpToDate, 2018

- Emile Bacha, Ziyad M Hijazi. Management of coarctation of the aorta. UpToDate, 2020

- Dijkema EJ, Leiner T, Grotenhuis HBDiagnosis, imaging and clinical management of aortic coarctation. Heart 2017;103:1148-1155.

- González-Salvado V, Bazal P, Alonso-González R. Aortic Coarctation With Extensive Collateral Circulation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11(8):e007918.

Authors: Michal Pazdernik, Mariya Kalantay

You Might Also Like

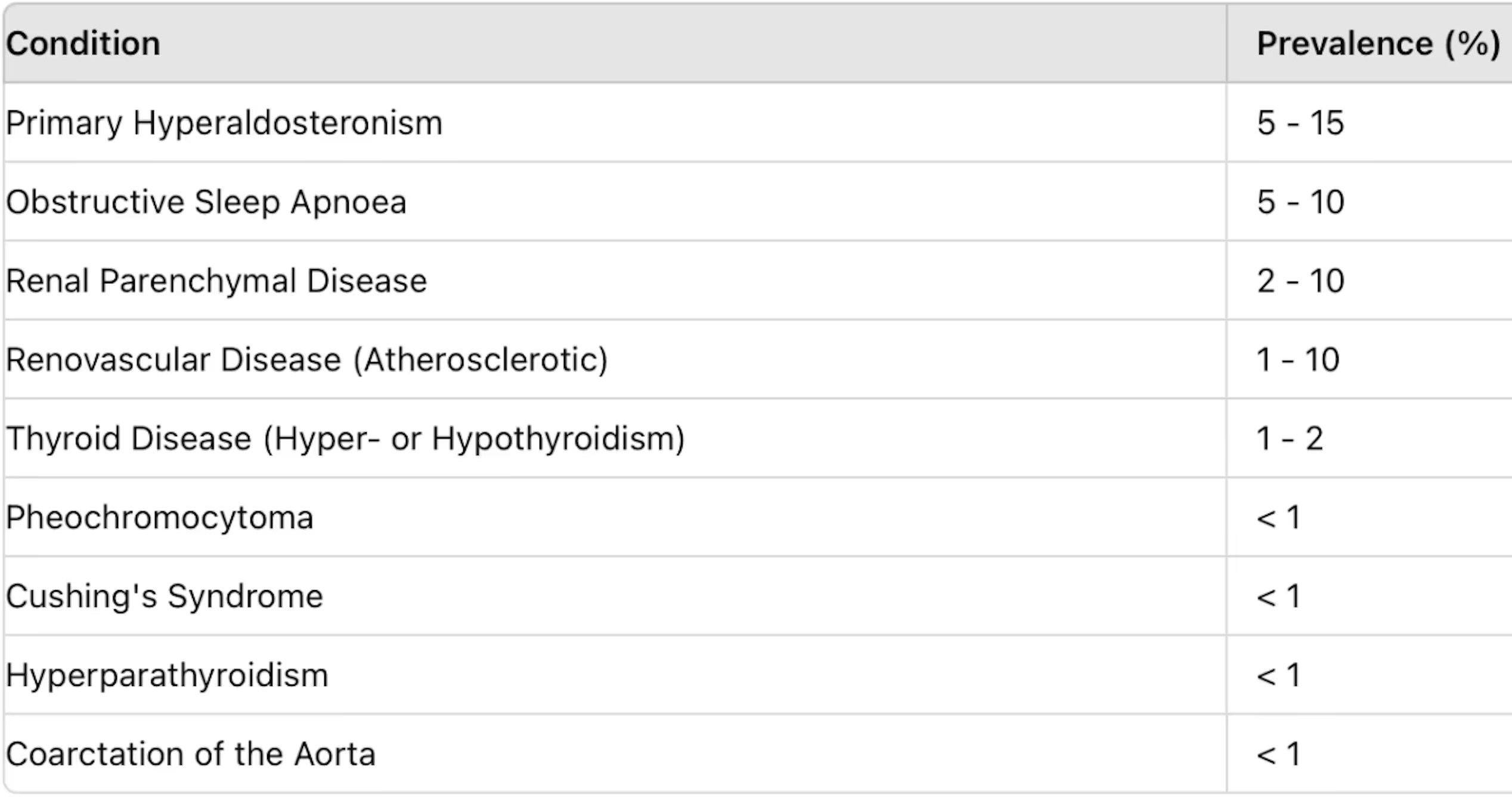

Secondary hypertension

Libman-Sacks endocarditis

.gif)